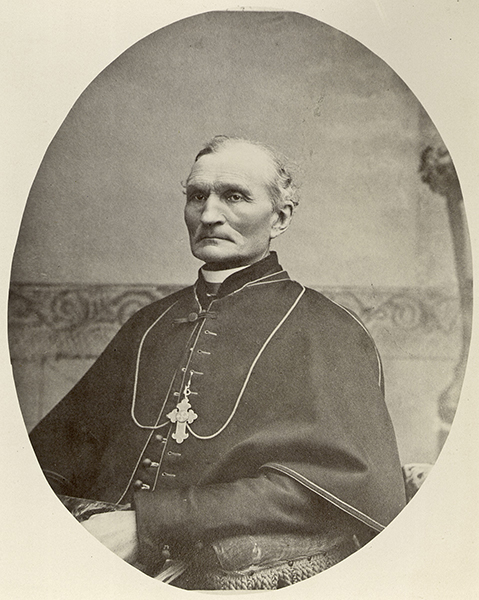

John Baptist Lamy, who arrived in New Mexico in 1848 to oversee the establishment of the American Catholic church in that territory, and who later became the first Archbishop of Santa Fe, set as his goal the "Americanization" of the people of New Mexico.

He felt that Catholic schools would be the best means for accomplishing this goal by not only educating New Mexicans, but also by providing a means for introducing "American" language, culture, and values. During this time of westward expansion and increasing European immigration, religious orders of women were at the forefront of Catholic education in the United States. Therefore, Lamy felt that a teaching sisterhood would best accomplish his goals in New Mexico, by bringing American-style schools, American Catholic practices and beliefs, and American culture to a people who had only recently become American citizens. In 1852, Lamy traveled to the First Plenary Council in Baltimore to find an order of religious women willing to take on the challenge of establishing schools in New Mexico. The Sisters of Loretto, a teaching order established in Kentucky in 1812, immediately volunteered for the task.

Despite a journey with many hardships, the Sisters arrived in Santa Fe in 1852 and established a school there. By the 1860s enrollments were dropping due to disturbances related to the Civil War and epidemics of smallpox. In order to increase both influence and revenues, the Sisters began to respond to requests by local clergy for schools in other New Mexico communities.

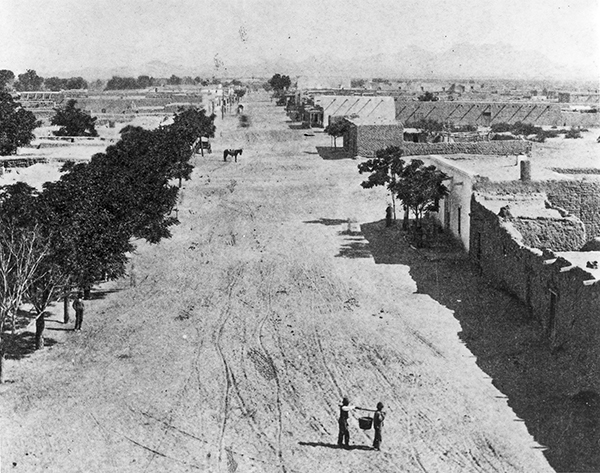

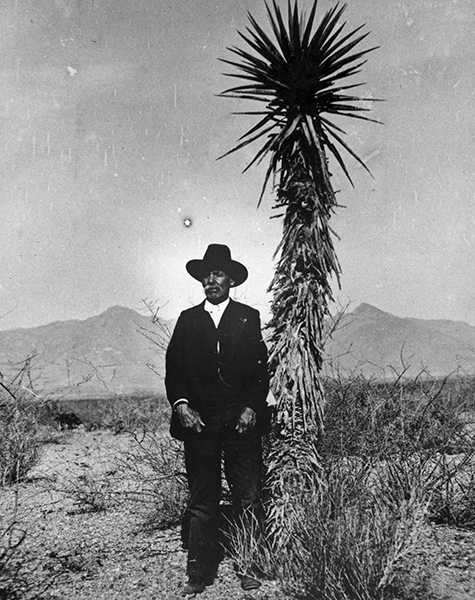

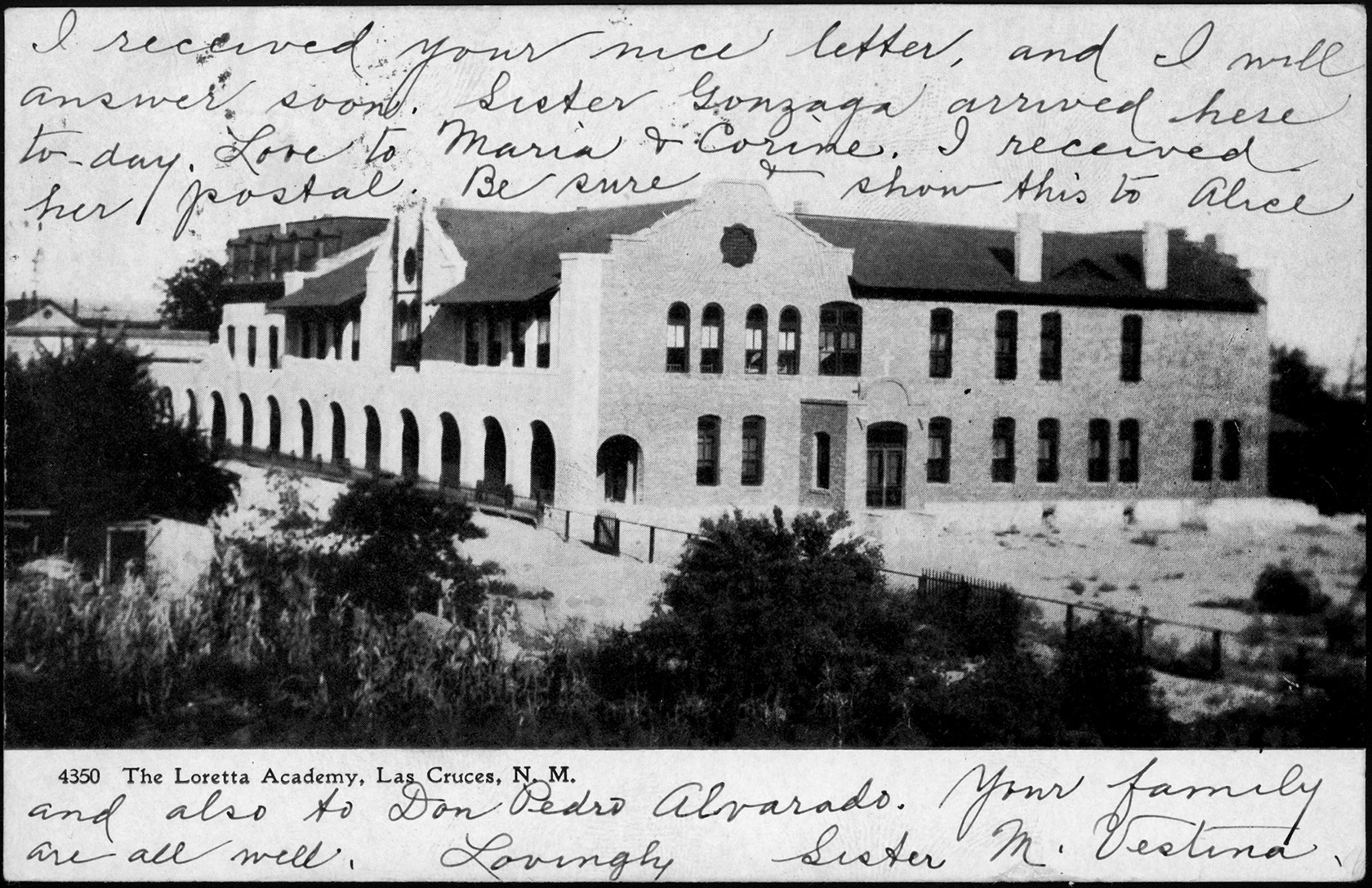

It was thus that the Sisters of Loretto arrived in Las Cruces in 1870. At that time, Las Cruces was a small agricultural community of around 1,300 people, 94 percent of whom were native-born. The majority of the population, according to census data, were school-aged girls who could neither read nor write, making Las Cruces an ideal environment for a school for young women.

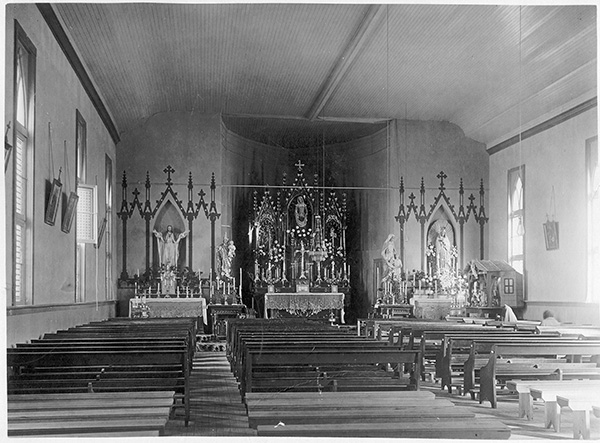

The first few years in Las Cruces were marked by hardship and poverty. Although the local bishop had purchased land for the academy, there was no building ready when the Sisters arrived. The Sisters accepted the invitation by Mrs. William Tully to begin teaching in her home. Upper-class families were impressed with the Sisters' school and many sent their children to be educated by them. When construction on the convent was finished the Sisters and their students moved into the new building. Until 1880 the chapel had only a rag carpet and the altar was composed of makeshift board and muslin. The floors of the convent were made of hard mud covered with rugs, and every five days the Sisters had to remove the carpets, clean them, and sprinkle the dirt floor with water. Meals consisted of bread, beans, and coffee made from parched wheat.

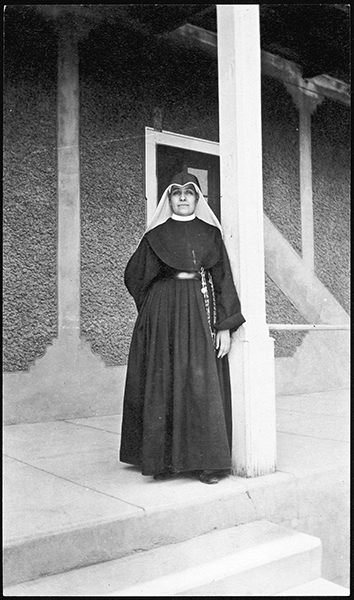

It was perhaps this poverty, shared with the surrounding community, that made the Sisters so accepted and so successful in their endeavors. The establishment of a convent in Las Cruces also eased the Sisters' integration into their new community by bringing local women into the Order. The foundation was set for the arrival of one of the most important figures in the history of the school to make her appearance in Las Cruces.

1880 brought the arrival of Mother Praxedes Carty to the Academy as the new Mother Superior. Mother Praxedes found that most of the town residents were poor and that the academy was still unfinished and in debt. Through bazaars, fairs, sales, charging tuition, and bank loans she quickly set about liquidating the debt. Mother Praxedes also used the court system to compel delinquent parents to pay tuition.

In 1886 Eugene Van Patten, the local tax assessor, sued the Sisters over a piece of property that he believed was being used for profit rather than for the benefit of the owners and residents of the Academy. The Sisters insisted that the land in question was a garden spot used to grow food for themselves and their boarders. Mother Praxedes testified in court as to the charitable aspects of the Academy, including feeding the poorer students with food from the gardens.

After liquidating the Academy's debt, Mother Praxedes began to improve the grounds of the school and convent. She also made improvements to the curriculum and religious components. Perhaps the most enduring result of Mother Praxedes' efforts was the one that directly contributed to the Las Cruces community: the rebuilding of their beloved Catholic church.

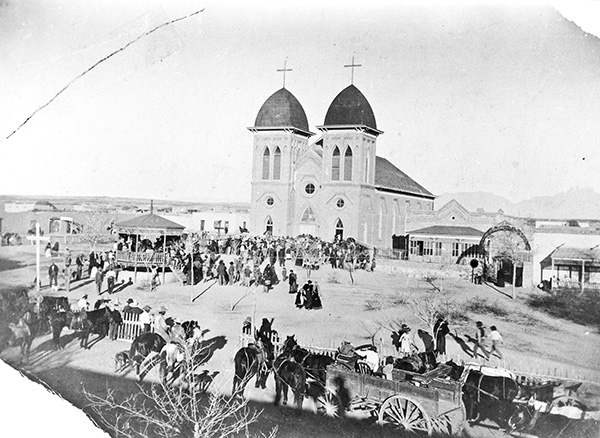

The church of St. Genevieve, was originally built in 1859. When Mother Praxedes arrived, it was an adobe building in dilapidated condition. In 1886, she decided to do something about the church, and with the aid of local citizens, convinced the pastor to erect a new church. An initial $3000 was raised through a subscription list. When funds became low, Mother Praxedes organized fairs or bazaars for additional money. By the end of the year, an imposing French-style brick cathedral with forty-four foot high twin towers had replaced the old adobe building.

Although the next several years brought many more improvements to St. Genevieve's, the church eventually began to deteriorate to the point where preservation and restoration seemed impractical. By the 1950s portions of the building were condemned by the state of New Mexico for unsafe conditions. For these reasons, and despite public outcry, St. Genevieve's was demolished. The site where the church once stood became a parking lot and later had a four-story building constructed on it. Although the demolition of St. Genevieve's was not part of the urban renewal program, too many Las Crucens are inseparably related. Today an iron statue stands in the downtown mall as a tribute to St. Genevieve's.

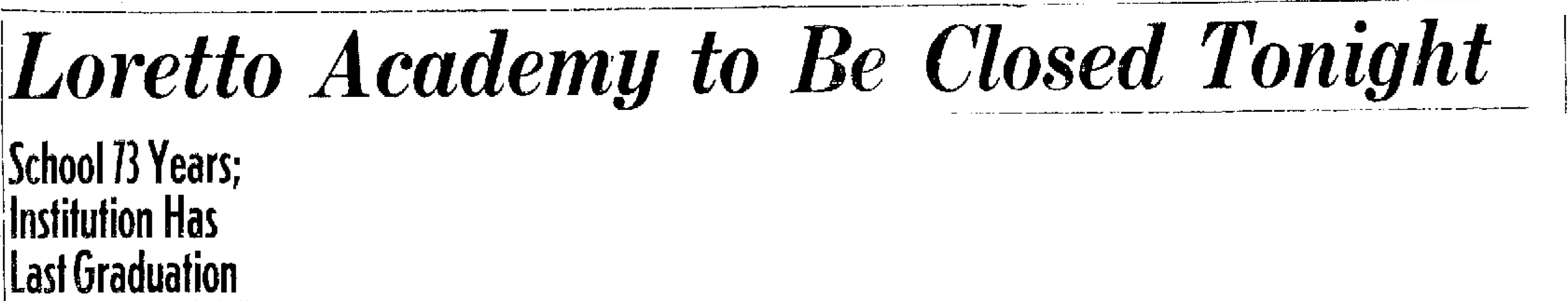

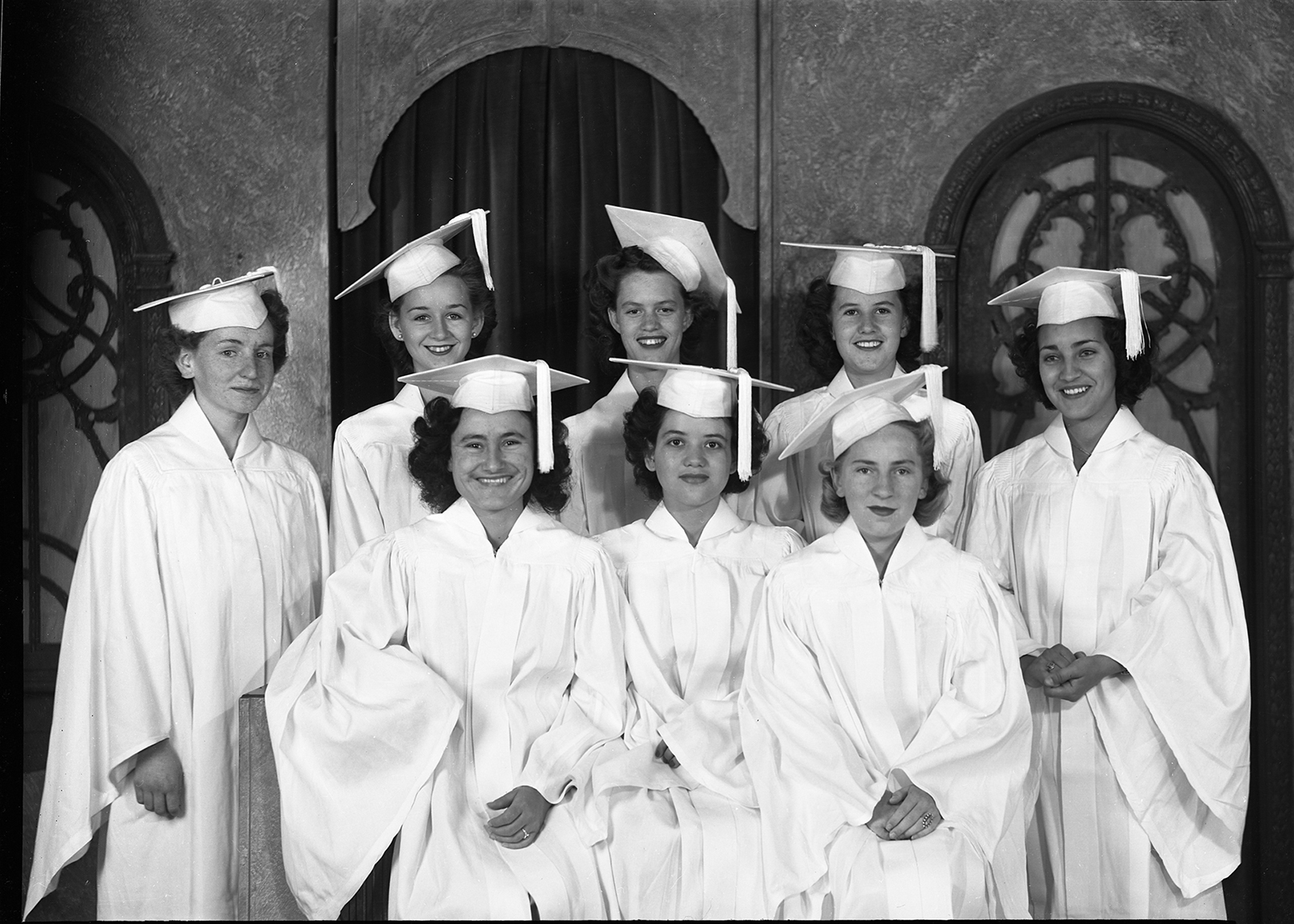

Loretto Academy's last graduating class The first three decades of the twentieth century saw an increased enrollment at the Loretto Academy, however, the end was near for the Las Cruces school. A new Academy in El Paso, founded in 1922, Loretto Academy's last graduating class drained students from the Las Cruces Academy, and the loss of students was exacerbated by disturbances on the Mexican border, the outbreak of World War I, and the Depression of the 1930s. The Sisters tried expanding the curriculum and offering more extracurricular activities to increase enrollment.

Efforts to save the Academy included the establishment of a parochial school in Las Cruces, Holy Cross. In September 1927 Sisters Frances Paula and Mary Lidwina opened Holy Cross school with an enrollment of 206 students. Although Holy Cross is still in operation today, the Sisters were removed from its faculty in 1945.

Despite the Sisters' best efforts, the Academy was closed in 1943. The legacy of the Sisters remains in their students, some of whom still reside in the Las Cruces community.

This section of the exhibition looks at the daily life of the students who attended the Loretto Academy in Las Cruces. The names and experiences of the early students, the curriculum in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the daily routine, and extracurricular activities are explored in some detail.

The first students to attend the Academy of the Visitation in Las Cruces were young women from wealthy and prominent Mexican American families. The names of these early students read like a roster of important leading citizens: Emilia, Josefa, and Clotilde Amador; Eleanor Fletcher; Carolina Islas; Amelia Duper; Josephina and Delfina Daguerre; and Mariana Ochoa. In later years, the students were increasingly drawn from the families of the Anglo citizens.

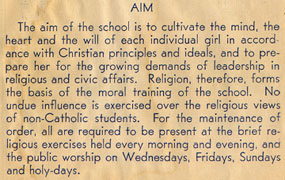

will be exercised over students of other denominations.

The Sisters' nineteenth-century students were primarily the daughters of tradesmen and businessmen, the most prominent in Las Cruces at the time. Tuitions were high and paid by the upper- and middle-class students which made it possible for poorer students to attend school for free or at a reduced price. Not only were the students economically diverse, but they were also religiously diverse. The arrival of Anglo Protestants in the Southwest changed the goals of the Sisters of Loretto. Their mission no longer was to educate only Catholics in religious and secular subjects, they desired to provide an education for any student willing to receive it. The Sisters also operated a separate school for boys from time to time. In the 1880s an average of sixty-four male students attended the school annually.

By opening the Academy to students of any sex, denomination, and financial situation the Sisters certainly added to their enrollment numbers and thus increased their revenue, but they also increased the educational opportunities for all children of Las Cruces, as well as children from other states and even other countries, such as Mexico.

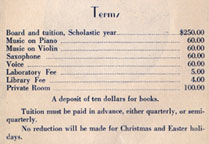

The curriculum in the nineteenth century consisted of typical Victorian female pursuits. Students learned the basics, such as arithmetic, grammar, reading, and spelling in the preparatory grades. At the high-school level, students studied more elevated subjects such as rhetoric, physics, analysis of poetry and prose, and ethics. Throughout the grades penmanship, composition, elocution, and physical culture were taught. From the Academy's foundation, its curriculum emphasized the arts and offered lessons in instrumental and vocal music, as well as painting and drawing.

The Academy was not training its female students to become physicists or professional musicians. The training was aimed at preparing middle-class girls for their roles as wives and mothers, with the possibility of a few years of teaching experience before marriage. A well-educated woman in the Victorian era was seen as thoroughly prepared not for a life of scholarship and study, but for the task of preparing their future sons for such a life.

from a 20th-century bulletin

As the times changed, so did the curriculum at the Loretto Academy. The twentieth-century curriculum began to include classes in commercial skills. These courses included typing, shorthand (in both English and Spanish), and bookkeeping. There were additional courses in business spelling, business correspondence, and a review of grammar, spelling, and arithmetic. This department was very popular and gave the female students skills that they could use to earn their own money after graduation.

The girls did not have chores, however, on Saturdays, they practiced mending their own clothes. Learning was thoroughly organized and systematically directed. If a student failed a test, the Sisters would give it to her again. Everything about an assignment was graded. Not only did the answer have to be right, but the penmanship, spelling, and punctuation had to be perfect as well. The students learned very quickly to be meticulous and never sloppy.

Although expectations remained that female students would work only until marriage, the establishment of a commercial department in the mid-1930s indicated that women's opportunities had expanded, and the Academy of the Visitation had recognized these changes and adjusted their curriculum to help their students take advantage of these new opportunities.

In the Loretto Crescent Emilia Amador Garcia gives some examples of life at the Academy in the nineteenth century. According to Garcia, the students led simple lives of lessons, recitations, and leisure activities. When lessons were recited the girls stood in a row, with the best scholars at the front and those who needed more help in the back. The time of day was measured with the help of hourglasses, and when the grains had moved to the opposite glass, classes were exchanged. In their spare time, the girls read, did fancy work, and engaged in conversation. In May, devotions were performed in which the girls presented flowers to the Blessed Virgin, and the congregations said the rosary and sang hymns. During the last week of June, the girls exhibited their sewing and works of art, and performed plays and recitations; and every girl was given a reward for completing the school year.

Elma Hardin Cain, who attended the Academy from 1934-1942 described life in the Academy in the twentieth century. The girls got up at six a.m. and in complete silence dressed, brushed their teeth, washed their faces, and combed their hair. Everyone would go to mass, then file down to the refectory and stand behind their chairs while grace was said. A bell would signal that students could sit down and talk and visit. After breakfast, a bell would signal and the girls would stand up, give thanks, and then go in silence to make their beds. Classes began at eight a.m. and were held for the rest of the morning. At noon the girls would get in line and repeat their breakfast routine which was followed by recreation until one o'clock. Classes were held again until three or three-thirty and recreation was enjoyed until four-thirty or five. After recreation was study hall, and then supper at eight o'clock. The younger girls went to bed after supper, while the older girls would stay up until nine.

During their recreation time the girls at the Academy could enjoy tennis, skating, listening to the radio, or reading. Music was a favorite activity and there were many bands including the Loretto Orchestra and Rhythm Orchestra.

After school activities for the students included organized sports. In 1909, a strip of land between the irrigation ditch and the convent was purchased and converted into a playground complete with basketball and tennis courts. The Athletic Club sponsored tennis and basketball teams as well as hiking and other sports.

In addition to organized sports, the Sisters provided special events and field trips for their students. The Sisters organized picnics and day trips to Guadalupe Ascarate's ranch, and they held annual exhibitions in which the students performed and entertained the community. There were also field trips to the new public library as well as to movies and lectures. The Sisters and their pupils were involved in the cultural life of Las Cruces in many ways.

One of the most significant aspects of the students' experiences was the close relationships that some developed with the Sisters. Juan Amador, a former student of their primary school for boys, kept in contact with the Sisters, including Mother Praxedes. Juan was not the only member of the Amador family to foster and maintain friendly relationships with the Sisters. Several pieces of correspondence between the Amadors and various Sisters can be found in the Amador Family papers at the Rio Grande Historical Collections.

The Sisters of Loretto laid the foundation for both the Catholic and public school systems that are in existence in Las Cruces today. In many ways, the girls and boys who attended the Loretto Academy in Las Cruces received an education typical of the times, one that developed and adapted to changing circumstances as the late 19th century gave way to the 20th century and the country approached World War II. The Sisters provided their students with basic skills, advanced subjects, extracurricular activities, and religious education. They also sought to introduce the language, customs, and values of the Anglo-American culture to their students and the larger community. Throughout their time in Las Cruces, they played a dynamic and important part in this southern New Mexico community, and indeed in the history of New Mexico and Las Cruces.

The Loretto Academy of Las Cruces was started in 1870 and closed in 1943. This collection includes, among other things, printed materials produced by the Academy: brochures, pamphlets, a graduation program, and two issues of The Loretto Crescent and The Loretto Chimes.